Open Office

Too close for comfort

I read this article, titled The Open-Office Trap, from Maria Konnikova’s blog at The New Yorker. It cites all sorts of studies and makes a pretty good argument that the Open Office is actually not a good place to get focused work done.

Since I personally work with people that are in other places (a distributed team) – and often even different time zones – I have heard many questions from people who work in a conventional office environment, curiously asking how that is even possible. To them, it feels so much more cumbersome, if not simply impossible, to work collaboratively with people when you aren’t able to get up from your desk, walk over to and ask someone something.

The more I hear these questions and think about good ways to reduce the amount of distraction and interruption, I find that it might actually be the other way around. I know, that sounds really counterintuitive.

The Problem: Thoughtlessness and the Sheer Amount of Interruptions

When David Craig surveyed some thirty-eight thousand workers, he found that interruptions by colleagues were detrimental to productivity, and that the more senior the employee, the worse she fared.

When I used to work at a media agency in Berlin, we had a nice open office space, holding somewhere around 15 or more people depending on the day of the week and currently ongoing projects. There were three directorswho each had their own separate office.

You can imagine that a lot of “quick questions” came up from the people working in the open office during any given day, me included. And so you’d walk over, stand in front of your boss’s glass door, looking inside to see if they were on the phone or typing at their computer. This act alone would most times get their attention (interruption/distraction already happening) and they would then either gesture you to come in or deploy some “give me five minutes“ body language.

Since you get conditioned by people coming to your door pretty quickly, you get used to keeping some attention in the corner of your eye, no matter what you’re doing. That’s like being partially distracted, most to all of the time. That is a weird form of subtle toxicity in regards to your attention span and ability to focus on deep(er) work.

On top of that, it’s not just the quick questions related to actual work that come in. You also get people just knocking, opening the door and saying things like, “Please call back Ms. so-and-so. They called earlier.”, or, “You want some coffee, too?”, and so on. Reasons are plenty.

The Solution: Raising Awareness and Getting Everyone to Be More Considerate

Architecture alone is not going to solve this. Having a (“gatekeeper”) secretary might also not work for everyone. So what can we do?

My conclusion is, you have to think and act more as if you are not being in the same place/office. That’s why I think it’s so valuable to be able and have the experience to work in distrbuted teams. It requires a different discipline. It forces you to consider efficient ways to get information to others or retrieve it from them.

And that’s really what TightOps is about. It makes a virtue out of necessity.

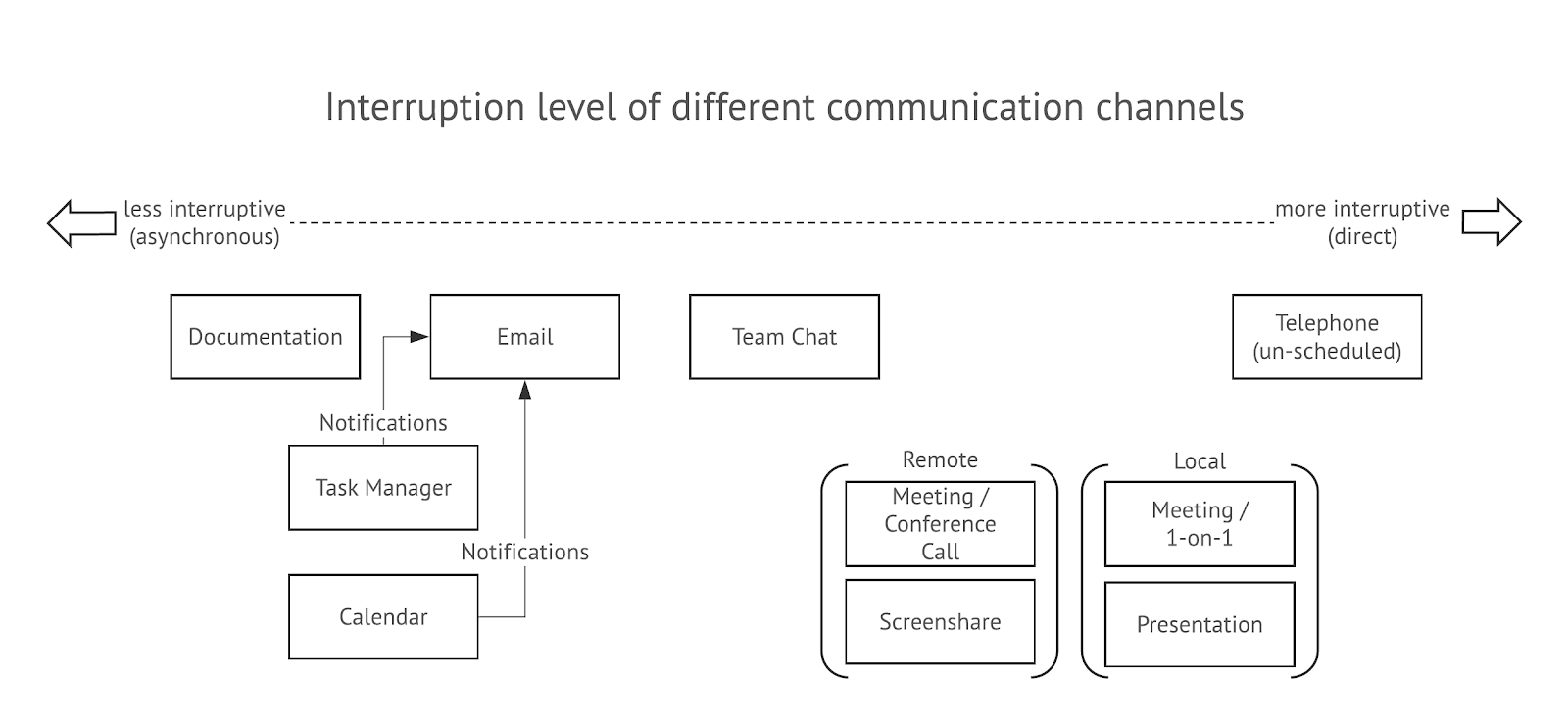

You start thinking about the “cost of interruption”, which we have illustrated with levels of interruption, where walking over to someone’s desk is on the far right of the spectrum:

Related and recommended here are the chapters from TightOps Fundamentals “How To Keep Interruption Low” and “What Goes Where”.